The Stanford Daily Search: A High Court Ruling

On April 8th, 1971, a large group of student demonstrators seized and occupied the administrative offices of the Stanford University Hospital. The 30 hour sit-in was in protest of the firing of a black employee, Sam Bridges. The following day, a clash between police and club-carrying demonstrators took place in the east end of the hospital, as police used a battering ram to break down the glass doors and file cabinets the students were situated behind. In the fracas, nine officers were injured, including one who was knocked to the floor by a thrown tape dispenser and then repeatedly struck in the head. Another suffered a broken shoulder. Protesters turned water hoses on the police, as the officers countered with chemical spray.

The next day a story describing the incident ran in the Stanford Daily, the campus newspaper. The article included pictures of the protest and indicated that a staff reporter with a camera had been reporting in the vicinity of the assault on the officers. Palo Alto police believed that photos might exist at the Daily that would provide the identity of the attackers.

So on April 12th, four Palo Alto police officers, carrying a Municipal court search warrant unexpectedly burst into the Stanford Daily’s offices. Police officers rifled through photographic laboratories, filing cabinets, desks, and wastepaper baskets. They read correspondences and inspected unpublished film.

On October 5th, 1972 U.S. District Court Judge Robert Peckham sided with the Daily. For Peckham, the fact that the Stanford Daily was not suspected of any criminal activity was pivotal. Indeed, many in the press cited the case as one of the few -- if only -- times in U.S. history that a newspaper not under suspicion of criminal conduct had been searched by police.

Peckham said that "the concomitant threat to the gathering of news -- which frequently depends on confidential relationships -- is staggering” and asserted that the U.S. Constitution bans police searches of newspapers, businesses or citizens not suspected of a crime. He said police should have sought a subpoena rather than a search warrant and awarded the Daily $47,500 for attorney fees.

After an appeal by the city of Palo Alto, a three-judge appellate court also sided with the Stanford Daily, adopting the opinion of Judge Peckham. Undeterred, Palo Alto appealed the case to the Supreme Court, which granted a review of the case. This brought national attention to the case. Advocates of both journalists and police ran editorials, op-eds, and opinion pieces in newspapers all over the country. What

had started as a quarter-hour Palo Alto police search had become the basis for a national debate over the freedom of the press.

On May 31st, 1978 the court stunned most judicial observers by overturning the ruling of the lower courts. In their ruling the court sanctioned police searches of news organization premises in cases where there is "reasonable belief" that material relevant to a criminal investigation is present. Writing for a 5-3 majority, Justice Byron White said that "Properly administered, the preconditions for a warrant ... should afford

sufficient protection against the harms that are assertedly threatened by warrants for searching newspaper offices."

But it would be press advocates who would win the final battle. Dismayed by the ruling, House and Senate Democrats, enjoying large majorities, pushed through a bill that effectively superseding the Supreme Court ruling. The law, signed in 1980 by President Carter, serves to protect the notes and files of nearly anyone preparing material for publication from a police search unless the person or organization is under suspicion of a crime or a life is in danger.

So while the Palo Alto police did receive the backing of the highest court in the land, the 357-2 House vote for the bill banning such searches proved that their actions had few supporters elsewhere. []

Our Reader's Memories:

"In reading your story of the

Stanford Daily Search Warrant, one important fact was left out. I was on duty at the Palo Alto Police Department on the day the search warrant

was served. A number of officers were picked for the assignment, but I

and other officers were assigned to a different task.

Before the search

warrant was obtained, a subpoena was issued for the production of the

photographs, but it was ignored.

The search warrant was

executed, but many, if not all, of the pictures had be either destroyed or taken to a different location."

-Wm Michael

Send Us Your Memory!

As Palo Alto police chief at the time of the case, the rather liberal Jim Zurcher is known for the conservative side of the Supreme Court case, Zurcher vs. Stanford Daily.

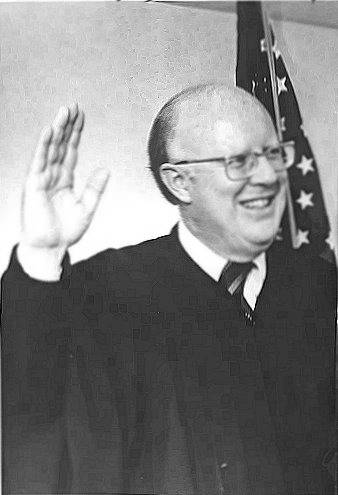

Judge Robert Peckham upheld the Stanford Daily's assertions. (PAHA)

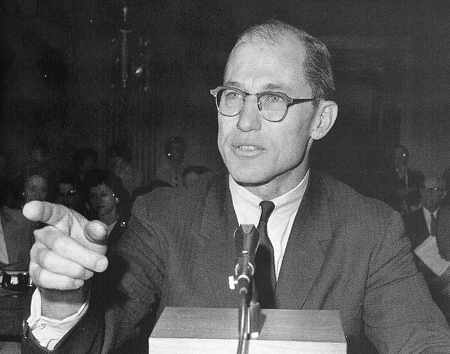

Byron "Whizzer" White was the Supreme Court justice who wrote the majority 5-3 opinion on Zurcher vs. Stanford Daily.

President Jimmy Carter eventually signed the 1980 bill that essentially overturned the high court's ruling.