The Barron Mansion Fire: Red-Hot Resentment

As the City of Palo Alto grew during the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, it began to annex the land to its south. The hotel area along old Highway 101 (now El Camino Real) and the neighborhoods south of Oregon Avenue became new Palo Alto acquisitions. But countrified Barron Park continued to hold out, voting down annexation a half dozen times during these years. Eventually Palo Alto took so much land nearby that it produced the cartographic oddity of Barron Park as a literal island of resistance to Palo Alto City Hall. Why was Barron Park so set against becoming a Palo Alto neighborhood? Much of the animosity dated back to 1936 when an enormous fire burned down the largest house in Barron Park and the Palo Alto Fire Department refused to help.

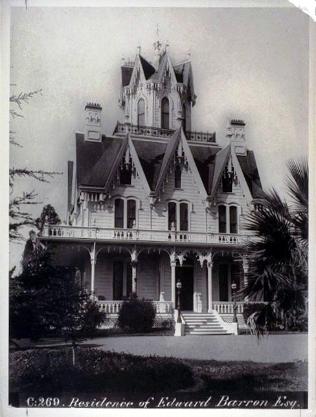

The Barron Mansion in Barron Park had been the pride of the neighborhood for many years. Originally constructed in 1857 on Mayfield Farm, it had served as a mansion for Sarah Wallis, one of the most prominent suffragettes in California. In 1878 it was sold to Edward Barron, the mining company executive. He added its famed octagonal fourth-floor cupola, as well as an enormous two storied west wing. The house also had two dining rooms, a billiards room, a two-story back wing for servants and a wide central staircase that welcomed visitors into the interior of the Victorian mansion. By 1936, the 26 room building had begun a new life as the Interdale School for Boys.

But in the late afternoon of November 29th, 1936, a fire began in one of the towers of the 80 year-old wooden house that would change Barron Park forever. While the cause of the blaze has long remained a mystery, electrical wiring was the likely culprit. Writer Joaquin Vienna first saw smoke pouring out of an upper-floor window while driving down the interstate. He turned into the estate, ran into the building and called the fire into three local fire departments.

Soon, fire crews from Redwood City, Menlo Park, San Mateo, County headquarters, and Moffett Naval Air Station were all racing toward the burning mansion. But it would be the reaction of the nearby Palo Alto Fire Department which would linger in the memories of Barron Park residents for decades.

Upon strict orders from the City Council, Palo Alto firefighters were not allowed to cross into other cities to fight fires because they might not be covered by insurance.

Although the nearest station to the fire was less than a mile away in Palo Alto, the fire crew there would only bring their trucks up to the end of the city line. Stopping at the border, 100 feet south of Wilton Avenue and El Camino Real, the Palo Alto firemen watched and waited. Meanwhile, Menlo Park and Redwood City crews, having to travel 7 to 9 miles further through Sunday traffic, crossed over the borders and finally reached the locale.

By the time they did, they found a ferocious raging fire that had begun to eat up the wooden structure. Menlo Park Chief Thomas Cuff took charge, but there was little the firefighters could do at that point, but try to save nearby houses. Furthermore, they could not locate a fire hydrant. Eventually they tore down fences and used a nearby recreational swimming pool in what would be an unsuccessful attempt to save the house.

During the futile battle, two county firemen nearly plunged into the burning building when they lost their footing on a ledge while directing a stream of water. No one was hurt in the fire, but despite the valiant efforts of the various fire departments, the mansion was totally lost.

In the days following the fire, heavy criticism was laid on the Palo Alto department and bad feelings continued to linger for years. Typical were the statements of one older resident speaking to Barron Park historian Douglas Graham in recent years, “They only were there to keep the fire from spreading into Palo Alto --- they didn't give a damn what happened in Barron Park"

Barron Park gas station owner Joe Weiler agreed, “Unfortunately and I hate to say this, Palo Alto was called and they didn't respond. They did come to the end of the city limits with one of their units...and just sat there. They wouldn't answer the call because they wouldn't go out of their district in those days. A lot of people were very upset at Palo Alto and still are today---the older people…still remember some of these things [as well as] the children of these people who have heard their parents talk about it."

Such resentment had a big effect on Barron Park’s future. When the annexation debate was raised in 1947, there was still a great deal of resentment from Barron Park residents toward Palo Alto. Despite support for annexation from the School Board and City Staff, Barron Parkers voted 338 to 261 to remain separate from

Palo Alto. By 1949, Barron Park had formed their own volunteer fire department and did not become a part of Palo Alto until newer, younger residents approved in 1975. []

Our Reader's Memories:

Be the First!

Send Us Your Memory!

The Barron Mansion before the fire. (PAHA)

The walls forming the garage at this house at 3878 Magnolia are the same walls that formed the pool that fire fighters used to fight the fire.

The current site of the old Barron Mansion, including the stone rememberance.