JFK at Stanford: Days of Decision

The assassination of John F. Kennedy brought the nation together in a profound way. In those still relatively early days of mass media, the country experienced its first hugely significant television moment on that November Friday in 1963. Millions of Americans sat in their living rooms looking at television boxes as Walter Cronkite tried to keep his composure announcing: “From Dallas, Texas, the flash — apparently official - President Kennedy died…some 38 minutes ago.” As in the days after 9/11, the country would unite in a way not experienced in years. Political grievances between Republican and Democrats, the differences between black and white, rich and poor — they all seemed suddenly, profoundly inconsequential.

Of course, it wasn’t just the shooting of the president and the confirmation of his death that mesmerized the nation, but the entire insane course of events that weekend. The arresting of Oswald, his bizarre and chaotic murder on live television, the apprehension of Jack Ruby, LBJ’s airplane oath next to Jackie in the blood-soaked dress, John-John’s salute and on and on.

Like the rest of the country, Palo Altans were jarred by the news. When an announcement was made to students at Palo Alto High School, the Palo Alto Times reported that “the assembly became a scene of anguish and hysteria. Some students wept openly, some cried out and others got up and raced out of the hall.” As events unfolded, much of the city was glued to their televisions throughout that surreal weekend.

The day after the shooting, the Times said that “the streets, the playgrounds, the stores, the schools — all were empty.” Inside, photos showed the Stanford Shopping Center and University Avenue completely deserted. Still, grief was evident despite the lack of people on the streets. In the downtown post office on Hamilton Avenue there was a black-draped painting of the slain president, while his portrait was displayed in many storefront windows.

Nearly everything in town was cancelled that weekend — the Mid-Peninsula YWCA dinner and theater party, Big Game parties at the Palo Alto Hills, Gold Country Club, and University Club, as well as No Trifling with Love, a production of the Stanford Players. Even the Big Game itself was postponed by a week for the only time in the long history of the contest. Incidentally, Stanford Coach John Ralston may have later wished he could take back his somewhat ill-timed comments that “There is no question in my mind that the added week will help us more than Cal.”

On Saturday night and Sunday morning, Palo Altans began to congregate in remembering their president. The Times reported a group of students at Cubberley High School who were up late Saturday night planning a special tribute to the late president. On Sunday morning, special services were held at the Foothill College Gymnasium and Stanford Memorial Church as well as at St. Thomas Aquinas Church, St. Ann’s Chapel, and St. Mark’s.

The local editorial page also mourned President Kennedy. The Palo Alto Times stated that “Today a shocked America feels an aching void. We shall deeply miss a courageous young captain.” Readers who wrote in to honor the fallen president were already trying to figure out who was behind the murder. One reader blamed “Dixiecrat racists,” another condemned “George Wallace and the John Birch Society,” and a third criticized “politicians and others who so glibly blame right wing extremists…while soft-pedaling the communist background of the assassin.” A debate had begun that lives on to this day.

Although certainly not all Palo Altans knew it at the time, the city had briefly played host to John F. Kennedy some 23 years earlier. During the fall of 1940, a young JFK had spent a few pivotal months at Stanford University as he audited business school classes and tried to figure out what to do with his life. It was a turning point for the recent Harvard graduate who at the time was being pulled in a great many directions.

Although he was the son of Joseph Kennedy, the wealthy businessman and Ambassador to the United Kingdom, young Jack was not necessarily the chosen son. That role had been reserved for his older brother Joe Jr., who was already at Harvard Law and seemed destined for great things. Not that the second Kennedy boy was any sort of black sheep. With some help from his father, he had already become a best-selling author after publishing his senior thesis on English appeasement as the book, Why England Slept. The Harvard yearbook had even named Jack Kennedy “Most likely to become president.”

But Kennedy was perhaps not as confident about his future as were his peers. For one, he was constantly battling health problems. Along with jaundice and digestive troubles, JFK had recently injured his back playing tennis and spent 10 days in bed at the Lahey Clinic. And Kennedy seemed a bit unsure about which career path to take. He had thoughts of becoming “an author or writer of some sort,” possibly following his father into business or maybe going to law school. Besides, as war loomed on the horizon, nobody Jack’s age really knew what the future held. So having heard his Harvard roommate Tom Killefer extol the beauty and climate of Stanford University, Jack figured he’d head out to California, get some warmth for his ailing back, and audit a few classes at the Stanford Business School while waiting to see what happened next.

In mid-September 1940, Kennedy arrived in Palo Alto in his brand-new cactus green Buick convertible with red seats and checked into the President Hotel on University Avenue. After getting a lay of the land, he rented the one-bedroom cottage behind the campus house of Miss Gertrude Gardiner at 624 Mayfield Avenue. For sixty bucks a month, it was a pretty good deal, plus he didn’t have to pay for a new bed — instead he took to sleeping on a plywood board at night to help his back.

As it turned out, Kennedy wasn’t really all that interested in business studies. Politics was clearly his field of choice, as evidenced by his hearty participation in Professor Thomas Barclay’s seminar analyzing the on-going 1940 presidential race as well as “Contemporary World Politics” with Professor Graham Stuart. He was fascinated with the war in Europe and not only because his father’s support for position incongruous with that of President Roosevelt. Jack actually had thoughts of his own on the war and they bent toward a much more hawkish stance than that of his father.

But despite his clear intelligence and interest in academics, Jack was also living the fast life for which the Kennedy men would become rather famous. Jack was well-known down on El Camino’s restaurant row, entertaining the ladies at L’Omelette and Dinah’s Shack regularly. His primary girlfriend at the time was Pi Beta Phi sorority girl Harriet “Flip” Price, but he was far less serious about the relationship than she wished. He dated lots of other girls, driving up and back to the city at dangerous speeds on Bayshore Highway. He also spent some time downstate with the Hollywood set, palling around with family friends like Robert Stack and meeting the likes of Clark Gable, Lana Turner and Spencer Tracy — and lots more girls. Perhaps tellingly, his favorite phrase in those days was “Slam, bam, thank you ma’am.”

During his stay at Stanford, the prospect of potential American involvement in the war continued to grow. In mid-October of 1940, the peacetime draft was enacted, a measure supported by Kennedy, who was a member of the Stanford National Emergency Committee. Kennedy registered on campus on October 18th, with some apprehension — not because he worried about serving, but because he feared he could not. Due to his bad back and other ailments, it seemed unlikely that Jack would ever be put in uniform. But as he wrote to friend Lem Billings, “They will never take me in the Army and yet if I don’t go, it will look quite bad.” A year later, family connections would help him become a Navy lieutenant where he won the Navy and Marine Corps Medal as commander of the famed boat, PT-109.

In the end, John Kennedy’s stay at Stanford would come to a rather anti-climactic end. A trip back east to help his father write his memoirs took him away from campus. Kennedy planned to return to Stanford for the spring term, but his passion and heart lay not at Stanford and the business school but in politics and World War II. Instead of returning to Stanford in 1941 he ended up travelling to South America and then making his way into the United States Navy.

Years later as those in Palo Alto mourned the passing of the president, there were many at Stanford for whom the tragedy hit especially hard. For they knew Jack Kennedy…

JFK working on Why England Slept.

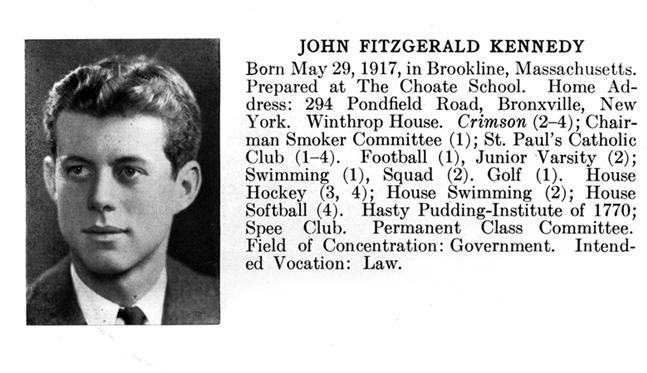

John F. Kennedy's high school yearbook entry.

After leaving Palo Alto, JFK would soon find himself in World War II onboard the eventually famous boat PT-109.

The bar at L'Omelette where JFK spent many a night.