Dinah's Shack: A Delicate History

Any story that portrays racial attitudes of past generations raises questions that deserve a hard look — even in these generally more enlightened times. Our country’s first leaders founded one of history’s great nations. They also perpetuated slavery and many kept slaves themselves. Our constitution has proved to be a brilliant and reliable document. It also counted each black man as 3/5th of a person. Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves and was certainly progressive for his day --- yet he was plainly on record in opposition to equality for blacks. When historians tell stories that reveal intolerance, how prominently should such prejudices be featured? Are these attitudes simply footnotes in history or are they the story themselves?

Such questions arise in Palo Alto's history in connection with one of its most celebrated restaurants, Dinah’s Shack. While the restaurant’s history ran for more than six decades, it’s hard today to look back on its conspicuous mammy logo, black stable-boy statues, and other slavery-era paraphernalia without feeling more than a little uncomfortable. And while the history of Dinah’s Shack tells the story of an extraordinary restaurant, it's hard not to think that the more significant story here — at least in a larger historical context — is of its paternalistic and stereotypical symbols and the blindness of whites who could not see their significance.

Dinah’s Shack actually began with a tribute to a black woman. In 1926, during a horse and buggy ride down El Camino Real, the old State Highway, Charles McMonagle and his wife Hazel saw an old ramshackle structure. According to legend, Hazel cried out, “It’s Dinah’s Shack!” — the home of the beloved black woman who had cared for her in her Kansas childhood. The McMonagles decided to buy the shack and turn it into a roadside carry-out restaurant catering to the many highway travelers on their way back and forth from San Francisco. They also purchased a 20-acre farm across the street where they grew the produce used in the restaurant.

In those early days, the restaurant was staffed almost entirely by black cooks and waiters, many of them former sleeping car porters, lured off the Southern Pacific. Dinah’s Shack featured the cuisine of the South, largely African-American influenced — Southern-fried spring chicken on toast, biscuits and honey, waffle potatoes — as well as musical acts such as Lou Foote and his Two Toes. Between the 1920s and 1950s, Dinah’s became a nationally famous stop along the old highway, known for “authentic southern hospitality,” as well as for being a favorite hangout for better-off Stanford students like John F. Kennedy, who was attending the business school in the fall of 1940. By that time, the McMonagles had introduced a kind of salad bar of hors d’oeuvres representing the cuisines of different states and regions of the country in which they often traveled to research local foods.

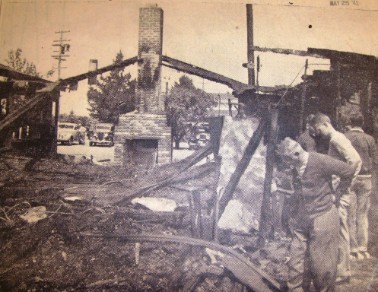

The ambiance of the restaurant was a selling point. Writing in 1936 in The San Francisco News, Ruth Thompson described “a large fireplace which on cool nights is cozily ablaze. Pictures adorn the walls; kerosene lamps flicker on shelves, on the old piano, on the mantel. Outside the gardens, there are attractive winding paths edged with fragrant blooms.” And when the entire restaurant, save the chimney, burned down in May 1942, the McMonagles managed to reopen within 48 hours in another shack — perhaps not quite like Dinah’s, but still on the property lot. Eight years later, they sold to John Rickey, the hotel owner and restaurateur who owned Rickey's Garden Hotel down the street.

Rickey brought a new layer of food and culture to the now 20-year-old restaurant. So-called Continental cuisine was featured in a “smorgasbord” which now took on a Scandinavian influence. While Dinah’s down-home cooking remained, it now shared the menu with Roast Duck L’Orange, Veal Cordon Bleu, and Salmon Dijonais — not to mention some 40 other smorgasbord appetizers, including rarities like marinated pig’s feet and pickled herring. Much of John Rickey’s famous if sometimes garish art was transferred to Dinah’s as well. The walls not only featured Leland Stanford’s personal art collection, but also many classic European sculptures which — according to 1980s reviewer J. Izzo Jr. — provided “a rich character that one can almost touch.”

Under Rickey’s tenure, Dinah’s was remembered warmly for many things, including dependable traditions. For instance, Phyllis Schlomovitz was a world-renowned harpist who served as Dinah’s nightly entertainment for nearly 20 years. Many still remember Winnie Coughlin, an 80-year-old waitress who worked at Dinah’s for more than three decades and was so beloved that she was often requested by regulars. There was also the famous wooden bar — kept intact since the fire — where customers carved their initials to mark their visit. Indeed, Dinah’s is remembered fondly by many as a favorite Palo Alto institution that thrived for decades, eventually becoming a cultural smorgasbord of harps, fried chicken and Swedish delicacies.

But what to make of its disturbing symbols? While the restaurant may have begun as a fond tribute to a black woman and the food she cooked, under later ownership and changing attitudes the slave imagery became troubling. By the 1950s, Dinah’s Shack seemed to suggest an almost misty regard for the era of Southern slavery. While Dinah's white patrons in the mid-century seemed oblivious, today a restaurant theme of happy cooking slaves would be enough to start a picket line.

In the first half of the 20th century, however, such images were common. For instance, Dinah’s mammy logo was reminiscent of the kindly slave and caregiver played by Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Wind and prominent for decades on the labels of Aunt Jemima syrup. Mammies were usually fat and jolly and they became iconic symbols of the Jim Crow South.

But the mammy character also symbolized a nefarious undertow in Southern society. As Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology at Ferris State University has written, “From slavery through the Jim Crow era, the mammy image served the political, social, and economic interests of mainstream white America. During slavery, the mammy caricature was posited as proof that blacks — in this case, black women — were contented, even happy, as slaves. Her wide grin, hearty laugher, and loyal servitude were offered as evidence of the supposed humanity of the institution of slavery.”

By 1968, blacks were gaining political power and speaking out against blatantly racist symbols of the day. Not surprisingly, the Palo Alto/Stanford branch of the NAACP went after Dinah’s. The group called the restaurant’s bandanna-capped mammy and stereotypically drawn stable boys “offensive,” while a group of professional journalists in a Stanford fellowship program publicly boycotted the restaurant because of its “offensive racist symbols” and “perpetuation of stereotypes.”

Responding to the criticism, Rickey does not seem to have really understood the objectionable meaning of the statues saying, “If they really feel it’s necessary, we’ll paint them white or make them Indians.” In the end, Rickey opted for this “split the baby” approach, actually painting the stable boys white and lightening the overhead mammy sign, thereby eliciting a mocking response from the local papers. One letter to the editor read: “It is a sickly, stupid attempt to ignore history and by hiding the black faces, to atone for the blackness of our own hearts.” Another: “Poor Dinah! Rest in Peace! Never again will I taste her ‘Southern’ fried chicken or her grand biscuits, as I cannot accept the hypocrisy of pink-cheeked stable boys.” Today a few of the whitewashed statues still stand, having outlasted the restaurant itself.

Finally succumbing to the economics of earthquake retrofitting, Dinah's was forced to close in 1989. Having long forgotten any racial controversies, the local papers wrote tributes to the restaurant, recalling its glory days and vibrant history. Some recalled that original story behind the Dinah’s Shack name. And perhaps in the end, having considered and noted the bitterness bred by caricatures of Dinah, we too should let our thoughts rest on the real Dinah and that day in 1926, when a white woman thought back to her youth and of her love for a black woman.

Dinah's in the early years.

Dinah's Shack in the 1980s.

The famed smorgasbord.

The painted-over statues still stand in the Trader Vick's parking lot.

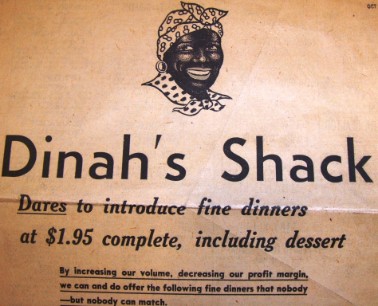

A Dinah's ad promotes a $1.95 full dinner.

The tower at Dinah's still stands.

After the 1942 fire.