El Palo Alto: Rooted in History

Every great city deserves a great symbol — some sort of natural landmark or iconic structure that looks good on the city letterhead and in tourist brochures while still recalling the city’s roots and history. The Statue of Liberty, Eiffel Tower, and Golden Gate Bridge are all man-made structures that represent proud cities in their most idyllic glory. But while Palo Alto is a lot smaller than the sprawling metropolises of New York, Paris, or San Francisco, it has a city symbol with just as much grace and dignity. This is the story of California’s oldest living landmark, the tree known as El Palo Alto.

Actually to fully tell that story you have to go back more than 1,000 years. El Palo Alto, the tall redwood that stands near Palo Alto’s northern border has been rooted to that spot for a millennium. It’s an amazing fact to consider. Today tree lovers can walk into a small park on the banks of San Franciscquito Creek and look up at this enormous redwood that was just a small sapling when Leif Ericson first set foot in the Americas. Indeed, El Palo Alto was past 500 years old when Christopher Columbus set sail and it was nearing its 800th birthday in 1769 when most historians believe Don Gaspar de Portola and his band of explorers first “discovered” the tree while looking for Monterey Bay.

Of course, if you visit El Palo Alto today, it’s difficult to get a sense of the landmark status it enjoyed in those early days of California exploration. Now it’s just one of many redwoods, oaks and non-native trees clustered near the railroad tracks along the Menlo Park border. But part of what makes El Palo Alto a perfect city emblem is that it transports one back to an earlier era when all that stood between the mountains and the bay were undisturbed grassy slopes and fields. A time when El Palo Alto was the tallest tree for miles around.

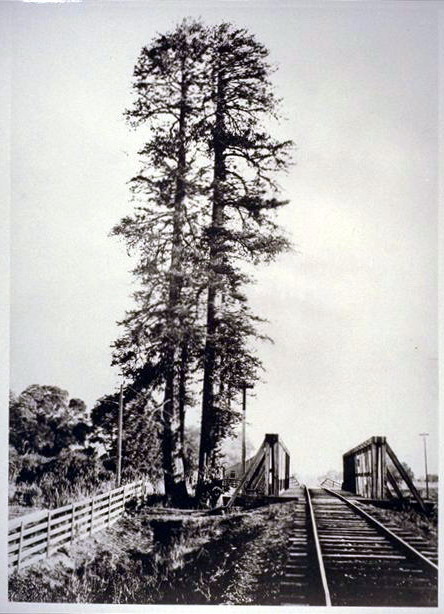

In those days, El Palo Alto had twin trunks standing side by side. One twin would eventually succumb to a mid-1880s windstorm, but a photo taken a decade earlier records the distinctive character of the twin tree that on a clear day could be seen from San Francisco. Mrs. C.F. de Ramirez recalled approaching El Palo Alto in the early days. As a little girl in 1837, she first saw the twin trunks from the hills in Belmont. She remembered that “it was a clear day and as we topped the summit of the hill, I saw the two noble trees, intertwined like brothers towering high above the oaks and buckeyes. In those days the twin redwoods were indeed beautiful trees, green and stately.”

Portola’s chief scout, Sergeant Ortega, must have seen it much the same way nearly 70 years earlier when he viewed the two tall trees from the high mountains near present day San Carlos. The Portola explorers had come up from San Diego in 1769 on a mission to search for Monterey Bay. But as early explorers had a tendency to do, Portola’s band got lost and found something else of significance — the San Francisco Bay. As the procession struggled down the hills they used the twin trees as a guide --- later camping beneath El Palo Alto between November 6th and 11th of 1769.

The twin trees that the Spanish called Palos Colorados (red trees) and later El Palo Alto (the tall tree) also served as a guide to other explorers. After camping beside the tree, Fray Pedro Font included El Palo Alto on his 1770 topographical map of San Francisco. “I beheld in the distance a tree of immense stature rising above

the plain of oaks like a grand tower,” he wrote in his diary upon first seeing the twin redwoods. And in 1776, Padre Francisco erected a cross beneath El Palo Alto to mark a proposed mission site, although Spanish engineers and military strategists in San Francisco eventually decided to build the mission in Santa Clara.

In later years, the city of Palo Alto would grow up under the scraggly branches of El Palo Alto. A century after the Spanish explorers took note of the tall tree, Senator Leland Stanford settled trotting horses on his new Palo Alto Stock Farm. Later he and his wife Jane founded a university that would model El Palo Alto on its official seal. And as the University Park tract matured around Stanford University, it incorporated in 1894 as the city of Palo Alto. The new city was already a stopping point for the Southern Pacific Railroad, which had laid its track lines beneath the natural landmark. The train depot less than a half-mile south at University Avenue became known to many as Big Tree Station.

Despite fondness for El Palo Alto, the tree has been in danger since it was first sighted from that hilltop. Poisonous train smoke and emerging farms certainly didn’t do the tree much good. Still, it was nature that did the most damage to El Palo Alto. During a particularly harsh winter in the mid-1880s, the tall tree lost its weaker half in a violent wind storm. When it came down, locals eagerly counted the rings and found the downed redwood to be 960 years old.

By the mid-1920s, many feared that El Palo Alto’s days were numbered. Issuing a kind of last rites, the local Native Sons of the Golden West hurried to honor El Palo Alto in 1926 — presenting it with a bronze plaque set in a granite boulder. But thanks to help over the years, first from Leland and Jane Stanford and later from the city of Palo Alto and local caregivers, great effort has been taken to preserve this hearty landmark. Soil and mulch have been filled in near the tree’s base, dead limbs are periodically cut off, spraying is done to combat tree pests, and a pipe runs up its trunk bringing water to mist the treetop.

Having weathered the railroad, loggers, floods, termites, wind storms and smog, El Palo Alto still stands along San Francisquito Creek towering over the city and refusing to die. So if you ever find yourself near venerable El Palo Alto, stop by and give that old tree a hug. After all, it's earned it.

The twin-trunked El Palo Alto in 1875. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

The Native Sons of the Golden West honoring the tree in 1926. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

The plaque placed by the Native Sons of the Golden West remains today.

A locomotive steams north past El Palo Alto. (Courtesy Palo Alto Historical Association)

The tree in 2008 with its misting pipe.